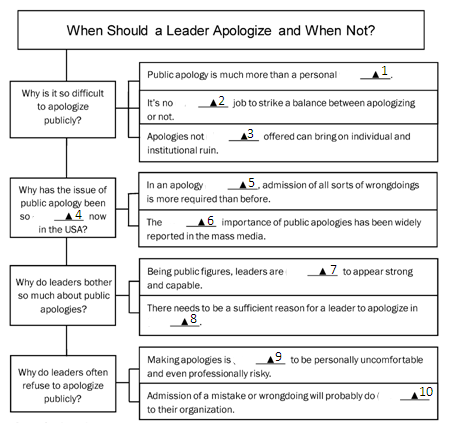

When Should a Leader Apologize and When Not?

Why Difficult?

When we wrong someone we know, even not intentionally, we are generally expected to apologize so as to improve the situation. But when we’re acting as leaders, the circumstances are different. The act of apology is carried out not merely at the level of the individual but also at the level of the institution. It is a performance in which every expression matters and every word becomes part of the public record. Refusing to apologize can be smart, or it can be stupid. So, readiness to apologize can be seen as a sign of strong character or as a sign of weakness. A successful apology can turn hate into personal and organizational harmony—while an apology that is too little, too late, or too obviously strategic can bring on individual and institutional ruin. What, then, is to be done? How can leaders decide if and when to apologize publicly?

Why Now?

The question of whether leaders should apologize publicly has never been more urgent. During the last decade or so, the United States in particular has developed an apology culture—apologies of all kinds and for all sorts of wrongdoings are made far more frequently than before. More newspaper writers have written about the growing importance of public apologies. More articles, cartoons, advice columns, and radio and television programs have similarly dealt with the subject of private apologies.

Why Bother?

Why do we apologize? Why do we ever put ourselves in situations likely to be difficult, embarrassing, and even risky? Leaders who apologize publicly could be an easy target. They are expected to appear strong and capable. And whenever they make public statements of any kind, their individual and institutional reputations are in danger. Clearly, then, leaders should not apologize often or lightly. For a leader to express apology, there needs to be a good, strong reason. Leaders will publicly apologize if and when they think the costs of doing so are lower than the costs of not doing so.

Why Refuse?

Why is it that leaders so often refuse to apologize, even when a public apology seems to be in order? Their reasons can be individual or institutional. Because leaders are public figures, their apologies are likely to be personally uncomfortable and even professionally risky. Leaders may also be afraid that admission of a mistake will damage or destroy the organization for which they are responsible. There can be good reasons for hanging tough in tough situations, as we shall see, but it is a high-risk strategy.

粤公网安备 44130202000953号

粤公网安备 44130202000953号